Rayan Elnayal Imagines Spaces of Hope and Serenity through Magical Realism

- Amuna Wagner

- Jul 16, 2024

- 8 min read

A full moon dangles from the ceiling, held by a hand in three thin strings, illuminating a room that floats in the afternoon sky. There are two banabeer, wooden framed seats strung with rope, on a red-green carpet; a tray sits on the smaller one, carrying jebena (traditional Sudanese coffee) and bakhoor (incense). Smoke wafts through the room and into the sky, merging with the clouds.

When I first saw this Sudanese spaceship created by Rayan Elnayal, I felt a deep affirmation that someone else out there was dreaming at the intersection of magic and future speculations. Her art offered me a vision I had not been able to grasp through my writing, through an approach I had not encountered before: speculative architectural design and a visual magical realism that is rooted in Sudanese culture.

Elnayal is a Sudanese architectual designer and artist, born and bred in London. She teaches architecture at the University of Greenwich and co-runs Space Black, a creative studio of Black built-environment professionals imagining alternative spatial futures for marginalised communities. In a video call she tells me that she always wanted to become an architect. While pursuing a master’s degree, she used her thesis and design project to deep dive into speculative futurisms and Sudanese architecture, both in Sudan and abroad.

“I felt disillusioned about the stuff I was told”, says Elnayal. “I didn’t connect with a lot of the terms, like modernism and postmodernism, because I didn’t feel that they represented what was important to me.” Still, she saw the potential and power in speculating and imagining alternative, better futures. “Futurism is a radical and important tool that can open up progressive discussions”, she says. “I don’t think I appreciated it until I saw how many white men were celebrated for it, and realised how important it is for us to speculate on our alternative futures, too.”

For her thesis and design project, Elnayal initially felt drawn towards surrealism and Afrofuturism, a cultural movement that combines science-fiction, history, and fantasy to explore the African American experience. “But both don’t feel quite right for me, because I’m not African American, I’m Sudanese”, she says. However, she credits Afrofuturism as an important first step in speculating futures that are more relevant to her life as a Sudanese woman. “If Afrofuturism hadn’t been created, we wouldn’t be able to react. It’s really radical and important for liberation to imagine alternative futures even if it’s slightly different to how we imagine our future. It gives us something to talk about that is still Black art, and that we have proximity to and can relate to in some ways.” But it still wasn’t what she was looking for, so she had to do more research.

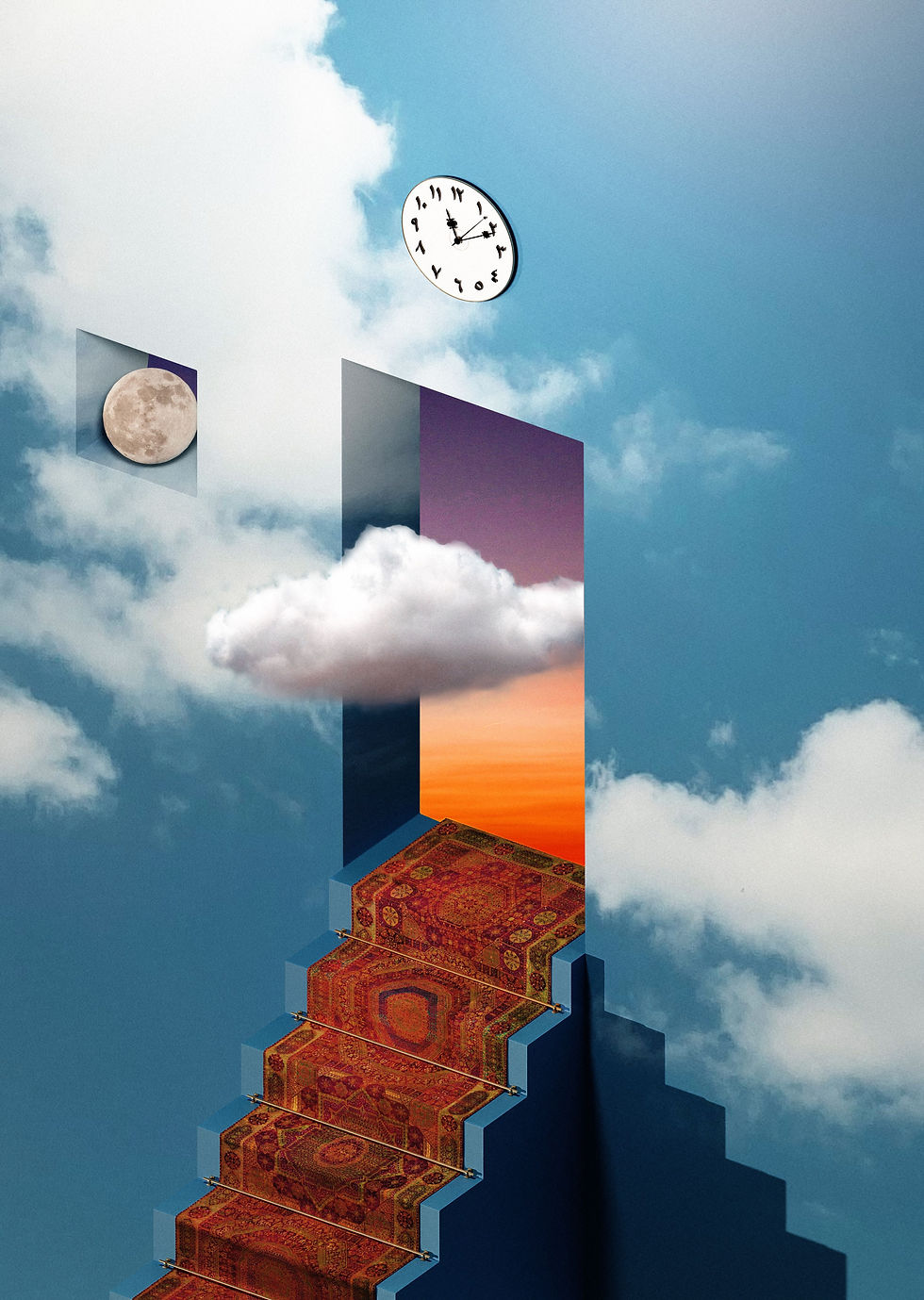

When Elnayal says that mainstream, as in white, Eurocentric and male, futurisms did not reflect her imaginations, she means that their speculations are based on a general assumption that everything will have to change and that time is a linear construct in which the future is not accessible to us yet. “To me that seemed so unrealistic”, she says. “A lot of modernism in architecture is built on that kind of grand macho futurism.” Instead of building whole cities, Elnayal’s designs re-envision intimate spaces, like interiors, courtyards, and gardens. She sees cultural practices that make up our everyday life now in the everyday life of our futures, assuming that “some things might not change and even if they do, they’ll stay familiar.”

Eventually, she fell upon magical realism, a way of storytelling that depicts the real world as having an undercurrent of magical and fantastical elements. While magical storytelling is part of many cultures, the term magical realism in particular is associated with post-colonial South American literature. “It better resonated with my way of thinking, because it’s not trying to be the dream that is surrealism, and it isn’t linear. In magical realist stories the beginning-middle-end structure doesn’t really exist”, explains Elnayal. “That’s how I saw speculative futurism, but also feminine spaces. They’re not grand and don’t exist in the hectic, unfamiliar futuristic narratives.” She found in magical realism an artform that is concerned with the mundane and it allowed her to create spaces that feel serene, magical, and normal.

Thus, the spaceship floating in the afternoon sky in which clouds merge with the smoke of bakhoor and the smell of jebena, visualises a tangible futurism that Sudanese people can recognize and look forward to. A peaceful, elevated morning coffee setting. “I like to create visuals that people can see themselves in”, shares Elnayal. “With the bakhoor and coffee, it gives it some sense of time, but also an activity to see how that space can be used. I don’t really put people in my artworks (I might start to), but I imagine people to step in and be the person within that space.” The piece, entitled Jebena, was inspired by a space in Elnayal’s grandmother’s house which was demolished and then rebuilt. “It’s not an accurate depiction, it’s based on my memory”, she says. “I tell people that that’s my version of a spaceship. In my eyes it is very contemporary, but it has all the things that make a Sudanese space. It reminds me of my grandmother as well, it’s quite feminine.”

Since magical realism has its roots in literature and film, Elnayal is vanguarding into unchartered territories. “In architecture, it hasn’t been explored at all, so it’s difficult to know what it looks like”, she says. “But it feels more fluid and reflects Sudanese architecture and identity, which is so diverse. It’s polyvocal and disagrees with the idea of one voice. We experience space differently and our reactions to it should be different.” Magical realist writing helped Elnayal gather ideas and gave her certain principles that grounded her when she needed it. “The key thing about speculation is that I’m not building, I’m just testing. I think it’s relevant in architecture and I’m excited to explore it.”

While the nation state of Sudan is not yet 70 years old, Sudanese history is ancient and incredibly rich. Sudanese literary writing and visual arts often entail magic, but are not overtly declared to be magical realist; the culture naturally lends itself to storytelling that makes space for several realities and narratives. “For artists and writers from countries that have had more than one coloniser, such as Sudan which was colonised by the Ottomans, the British, and the Egyptians, one linear way of thinking becomes difficult, because of the parallel realities they hold”, says Elnayal. Due to its geographical location, Sudan is sometimes considered to be part of North Africa and sometimes belongs to the East; it is officially Arabic-speaking, but also home to 99 other languages, and inhabited by several ethnic groups who practice several religions. “Sometimes people see magical realism as messy or chaotic, but I see it as a canvas that has to accept many different textures, colours, ideas, and voices at the same time”, says Elnayal. “When it comes to Sudan, there can be no monogamous way of speculating.”

Elnayal begins her art practice on a blank canvas, too. She approaches her creations through a feeling or a memory, rather than a clear vision. Mixing media and historical references, she uses 3D tools as well as 2D collages, draws plants, traditional furniture, cats, windows and watches. “I don’t try and understand what it will look like fully”, she says. “There aren’t many references from the profession to fuel ideas or back up arguments, which creates a space where it could be anything. The more I create, the more I realise it’s really important to speculate on those futures however small, however fictional.” This statement holds true in regards to both her homes.

Becoming an architect in the UK is an extensive process and as a result, Black people are less likely to graduate with a degree in architecture or even gain access to it in the first place. “It’s difficult to compete and there’s a huge lack of diversity, which means there’s also a huge lack of diversity in thinking and funding”, says Elnayal. Thus, while speculation is a prominent practice in Africa and the diaspora, the field of architecture lags behind in accommodating non-white, non-male voices. This is not merely a concern of representation; as long as the speculative space is being driven by white men, a lot of harmful space is being built and marginalised people have their lives endangered.

As a teacher, Elnayal encourages people of marginalised backgrounds and identities to contribute to conversations and explore together. “[Mainstream] futurism doesn’t accommodate us, but it creates some sort of progress and discourse within the design and art space which sometimes leads to practical solutions”, she says. As an artist, she wants to grant herself and others the opportunity to have fun and experiment. “Women and gender minorities within design have struggled to put their ideas forward, because it requires an audacity that we’re sometimes not allowed to have and there’s pressure to produce the perfect idea. But there’s so much value in creating what you consider to be rubbish work”, she says. “I always tell people that a lot of these white men, who are now deemed to be pioneers of design, practised or presented their ideas in extremely problematic ways. But now they’re still celebrated, sometimes more than they should be.”

In the case of Sudan, exploring speculative futures is equally crucial, but (at best) ironic in the face of ongoing destruction and uncertainty. Elnayal, like many others, has struggled to create since the outbreak of war in Khartoum, the capital of Sudan, in April 2023. Both her generational homes have been lost, damaged, or looted by the RSF militia and the army. “Ever since then, it’s been difficult to imagine a future that could be different to what it was before”, she says. “It’s been very difficult to create from a place of joy, which I usually used to.”

As Sudan is losing documented culture, history and art to the armed conflict, there’s an urgency to replace, replenish, and maintain cultural production. Elnayal bases much of her work on documents and photographs she took of Sudanese architecture. “It’s difficult to get royalty free photography in Sudanese architecture”, she says. “So I used to just take pictures for my own practice. Now I realise that I have very important documentation, unfortunately only of the tricity: Khartoum, Omdurman and Bahri. I never managed to expand that photography.” As the war continues with no end in sight, private photographs saved on hard drives and phones have become invaluable archival material. “I think that my practice will have to adapt”, says Elnayal. “It’s important to be able to retell our stories with artwork, writing and music. I think it means expanding the mediums we use, not to stick to the one medium that we feel comfortable in. It’s a reaction that happens in these kind of situations.”

On Sudanese architecture, Elnayal mentions the importance of preserving the traditional use of space. For example the lively happenings of a courtyard, or the expansion of a Sudanese home to accommodate a married couple. She also believes that the collective Sudanese mind is shifting and expanding. “This war has made people realise what they did wrong, what voices they didn’t include or listen to. What parts of Sudan we didn’t listen to as privileged people. Because there are states, most of all Darfur, that went through war for much longer than Khartoum did.”

As Sudanese artists are burdened and entrusted with the responsibility to preserve and document the country’s history while imagining hopeful futures, Elnayal’s Jebena becomes more important with every day the war rages on. At times it feels like magic will be needed to heal the pain and stop the destruction; her art is a reminder that Sudan harbours this magic.

Comments